Plumbing the Mysteries of the Adriatic

Plumbing the Mysteries of the Adriatic

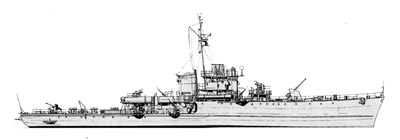

Le Terrible. ©Achille Rastelli. Private

collection

In September of 1943, after Italy surrendered to the Allies, German forces requisitioned a number of Italian navy units, mainly destroyers and corvettes, which, for various reasons, were unable to reach Malta and other ports in south Italy where the fleet had been ordered to group. The over sixty units that fell into German hands were given names bearing the initials TA or UJ followed by a number. TA stood for Torpedoboot Ausland or “captured torpedo boat;” UJ stood for Unterseeboote Jager or “sub hunter.” These units, integrated into the Kriegsmarine, and split into various flotillas, bravely resisted the advance of the Allies in the northern Mediterranean. They were all sunk during the last year and a half of World War II.

From this group, many of the ships that sunk in ports or in shallow waters were salvaged and scrapped immediately after the war. Some, however, are still underwater and have been the focus of research projects by the Wreck Diving Society (WDS). WDS is an organization based in Italy aimed at promoting a general interest in both naval history and archaeology through the research and documentation of underwater wrecks and wreck sites. WDS members include researchers, archaeologists, journalists and GUE-trained divers.

The following article discusses the fate of a few of the Kriegsmarine “Ausland” units that now lie on the bottom of the Adriatic Sea.

|

“Frechdachs” was the name of a top-secret operation conducted in February 1944, designed to provide vital supplies to German troops fighting under desperate conditions on the Aegean islands. After careful planning, a large freighter, the Kapetan Diedrichsen, under the powerful escort of destroyers TA-36 and TA-37, corvettes UJ-205 and UJ-201, and three motor minesweepers, left the port of Pola, Croatia, immediately after sunset on 29 February 1944. They were to attempt a dangerous journey along the Adriatic and Ionian Seas, an area already controlled by Allied naval forces. A few hours following its departure, the convoy was spotted on the radar of two Free France navy light cruisers, Le Terrible and Le Malin. That same morning, the French cruisers had left their base in south Italy on a patrol mission to intercept German seagoing traffic. Having the advantage of radar, the Allied ships attacked the convoy at high speed, firing with all their guns. In just a few minutes, the Kapetan Diedrichsen, the TA-36 and TA-37 were all badly damaged, while the UJ-201, hit by a torpedo, sank with no survivors. A few hours later, the Kapetan Diedrichsen also sank due to the damage and fires caused by the attack; the TA-36 and TA-37 made it back to Pola in critical condition.

The TA-36, an Italian “Ariete” class torpedo boat, formerly named the Stella Polare, sank two weeks later, on 18 March 1944, after hitting a mine in the Quarnaro Gulf, Croatia. There were no causalities. Her beautiful wreck was discovered by a local diver in sixty-six meters of water and identified by WDS divers in the winter of 2000.

UJ-202 bow

On the night of 1 November 1944, a Kriegsmarine naval force

composed of TA-20, UJ-205 and UJ-208 entered the Quarnerolo

Channel, heading south towards the port of Zara to evacuate troops.

The Quarnerolo Channel lies between the islands of Pag and Lussino.

At the same time, two Royal Navy Hunt class destroyers, the HMS

Avon Vale and HMS Wheatland, were entering the channel from the

south heading north. They were on night patrol in search of enemy

forces in hostile waters. They were running single file, a few

dozen meters offshore of Pag Island, scanning the sea surface with

their radars. About five miles north of the village of Novalja they

spotted the German naval party on their radar. The two destroyers

turned toward the middle of the channel, increasing their

speed.

UJ202-gun

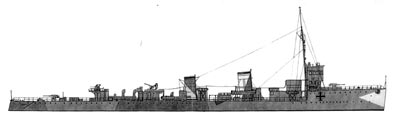

UJ-202 Illustration by Dr. Daniel Frka

A couple of minutes later, a white star shell illuminated the channel and the outlines of the German ships; a barrage of gunfire from the British destroyers’ four-inch guns quickly ensued. Though the German ships responded with all they had, the advantages of radar proved insurmountable during nighttime battle. After only ten minutes, the two brand-new Kriegsmarine corvettes were reduced to burning wreckage and, engulfed in explosions, rapidly sank to the bottom. The TA-20 turned its course, seeking to escape towards Arbe Island (located north of the channel). It did not succeed; it was hit and destroyed by gunfire. She sank in the dark channel waters less than thirty minutes after her companion ships were sunk. British destroyers picked up 71 surviving German crewmembers from the water; these, together with another 20 men rescued by German ships the following day, were the only survivors from the fighting.

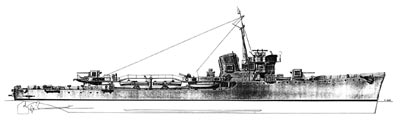

TA-20 Illustration by Dr. Daniel Frka

UJ-202 |

One month later, on 12 December 1944, two other Royal Navy Hunt class destroyers, the HMS Atherstone and HMS Aldenham, were on mission in the same area. They had orders to shell the towns of Karlobag and Pag, as well as other German strongholds and artillery emplacements on the mountains along the coast, in support of the ground action of Marshall Tito’s Yugoslavian troops. The shelling ended without incident for the Allies. Returning to base, the HMS Aldenham hit a mine. The explosion broke the destroyer in two, and she sunk within minutes. One hundred and twenty-three members of her crew died. The HMS Aldenham was the last unit lost by the Royal Navy in World War II.

Partisan M. Arena |

It has taken WDS years of researching archives, reading books and examining registers to accumulate details of these stories. As we amassed information, this fleet became one of our main targets.

Our efforts to locate the wrecks were partially based on historical accounts of the fighting. However, as was often the case, such records proved inaccurate as a result of the confusion generated during nighttime fighting in the open sea, fighting which often ended with ships being sunk, without surface trace, in just a few minutes. To remedy this we matched the historical data with “signs” found on trawler fishing boat charts. This furnished us with a number of “presumed points” from which to start survey patterns with a standard echo sounder. The trawl net fishing charts in Croatia are typically photocopies of nautical charts on which boat captains identify points where nets—his own and of other fishing vessels—get damaged, entangled or lost over the years as a result of obstacles on the bottom. These points are taken with radar triangulation, measuring the distance of the point at sea from two main points on land. This method yields minimal “precision,” as sometimes pen signs were a half a mile long or more. We tried to correct the errors, taking into acccount the differences between the geographical coordinates from the chart of already known points and GPS coordinates of the same point, but in most cases this only got us close. The real work required hours at sea with an echo sounder and a bit of luck. Despite this rudimentary system, during their years of activity in the Croatian Adriatic Sea, WDS divers managed to find fourteen major shipwrecks, many other minor vessels, ranging from a little tug boat to motor mine sweepers, fishing boats and, of course, an assortment of trash.

TA-36 Illustration by Manlio

Gay

Between the summer of 1999 and the winter of 2000, WDS divers started focusing on the Quarnerolo channel, organizing a number of weekend projects that sought to locate wrecks. The first wrecks we found in the area were the Austrian Lloyd freighter SS Albanien in 72 meters (238 feet), and the Austro-Hungarian troop carrier SS Euterpe, in 79 meters (260 feet); both of these were sunk during World War I. Shortly thereafter, we found the TA-20, formerly the Italian RN Audace. She lies in an upright position in 80 meters (264 feet) of water; she is largely intact from bow to stern, but badly damaged. The RN Audace was an Italian destroyer that also participated in World War I. She has some particular importance, in that immediately after the war, she was the ship repeatedly chosen by the King of Italy to visit Italy’s newly acquired territories. Discovery of this wreck raised a great deal of interest on behalf of the Italian media.

The next wreck discovered by WDS divers was the bow and bridge sections of the HMS Aldenham. Found in 85 meters (280 feet) of water, the bow lies on its left side, partially buried in the soft mud of the bottom. Visibility on the wreck was always very bad, ranging between 0.5 to 3 meters (1.6 to 10 feet) on each dive.

During the same period, a WDS

researcher contacted a number of survivors of the HMS Aldenham crew

and some relatives of crewmembers who died in the sinking. In the

more than ten letters WDS received from them, the tragedy of the

sinking was brought to life. The WDS, together with the veterans

and their families, decided to place a bronze plaque on the wreck

in memory of the one hundred and twenty-three brave sailors and

officers who lost their lives.

During August of 2000, WDS decided to organize a fourteen-day

project in the area, based on the island of Pag. The

project’s objectives were to find the wrecks of the corvettes

UJ-205 and UJ-208 and the main section of the destroyer HMS

Aldenham, and to survey and video all the wrecks in the area.

Organizing logistics for eleven divers involved in a deep wreck exploration project on an island proved challenging. In the end, we managed to set up a potent mixed gas filling station supplied with plenty of breathing gases, have our portable double-lock hyperbaric chamber system set up and ready for emergencies, find two boats to use and a third available in case of emergencies, hire a cook to ensure that food was ready to serve fourteen hours a day, and obtained permission from all the appropriate authorities associated with an official research project in Croatia. The project ended up being a collaborative effort with the Ministry of Cultural Heritage of Croatia, and was aimed at locating, surveying and documenting area wrecks.

After we set up, a general diver briefing was done. It included filling operations and safety, boat operations and safety, and hyperbaric system operation and safety. Four of the divers were also hyperbaric technicians.

The eleven divers were split into two exploration teams of three divers each and two safety teams. Planned operations had one exploration team at a time in the water from the main boat, one safety diver and one captain on the main boat, and one safety diver and one captain on the chase boat. One hyperbaric technician was always on land in radio contact with the main boat, while the other divers were filling tanks and setting up the equipment at the peer for the next dive. At the end of a dive the two boats returned back to the peer, where the teams changed and the material for the following dive was loaded. This system worked very well, so well that on some days we managed to have one team doing a repetitive dive. The real limitation in this system was the compressor’s capability to fill the tanks needed. We ran the compressors for twelve hours a day.

|

|

The project began with an exploration of the wrecks that had already been located. On the first dive on each of these wrecks, a fixed down line was established before we began surveying and filming. Dives were 70 to 80 meters (231 to 264 feet) with average bottom times of 30 minutes. Exploration divers carried all their required decompression gas with them, and spare decompression tanks were on both boats. We received a daily visit from archaeologist Jasen Mesic, reaching us either at sea or at our base to review the video shot and hear about our reports and new findings.

Our search for the other wrecks, using an echo sounder, began every

day after the end of the second or third dive, and continued for

some hours at night. Thanks to the thermal

|

|

We dedicated the day following our discovery to the first exploration of the two Kriegsmarine ships. UJ-202 and UJ-208 were former Italian Gabbiano class corvettes, the RN Melpomene and RN Spingarda. Their wrecks, at a depth of 80 meters (264 feet), were an impressive sight, in part due to the particular visibility conditions. The first 75 meters (247 feet) from the surface were very clear with optimal visibility; the last few meters to the bottom were a cloud of mud. Some sections of the wrecks came out from this cloud and appeared suspended in the crystal water, as if appearing from a dense fog. The first wreck we visited revealed some of the details of her sinking; her stern was partially destroyed and driven into the mud, the bow’s keel was raised at least three meters from the sea floor and pointed towards the surface at about a 40° angle. Most probably, a direct hit blew up her stern which, followed by an explosion of the mines she was carrying, caused her to sink stern-first to the bottom. Her 100 mm bow gun is pointing crosswise to the right, indicating that, before sinking, she had reversed course back to the north, while firing at the enemy. On the stern there are a number of mines still hooked to their mooring systems, and there is no trace of the bridge or of the aerial mast; both are completely missing. The other ship is on her right side, apparently intact from bow to stern; the bridge is in place and several anti-aircraft guns point in every direction. This ship is almost completely immersed in the mud cloud and offers very little visibility.

With only two days left before the project ended, the main section of the HMS Aldenham was still missing. Despite the many hours we had already spent searching with the echo sounder in the zone of her sinking, and despite the fact that we had used the location of the bow section as the starting point, and not a "presumed point," the sea was not revealing its secrets. At this point WDS divers were quite frustrated and had begun thinking that the stern section could have been entirely blown up or salvaged after the end of World War II. The team reviewed the reports of her sinking, trying to imagine all the possibilities. According to witnesses, the stern section sunk with the propellers still moving which would indicate that the section included the engine room, and hence would have to measure 40 to 50 meters (132 to 165 feet) long. We had to find it. In search of information, we decided to spend a morning in the village of Novalja, in front of the point where the Aldenham sank. The idea was to approach fishermen and ask them for information about obstacles on the bottom in that zone.

After some research at the local fish

market, a man took me to the house of a retired fishing boat

captain who proved to be the right man. During the war, he had been

a young partisan with the Yugoslavian resistance and had witnessed

the sinking of the HMS Aldenham. Together with many other Novalja

residents, he had gone to where the vessel sank to try to help

rescue survivors. He said that the local partisan command had

spotted the presence of mines in the area some days before the

sinking, and had warned Allied Naval Command; apparently the latter

ignored the warning. After the war he spent his entire life on

trawl fishing boats. In those days the fishing boats were not

equipped with radar, nor did they have any other electronic device

for navigation; all the trawling routes were maintained with sight

alignments on the coast in order to avoid the known obstacles on

the bottom. He had “a hundred alignments in his head.”

The former partisan, and retired captain, agreed to take us to the

wreck, which in his memory was in one piece.

Having this 72-year-old man on board helping us locate the wreck

was an experience in itself; he was our living link to the past and

to the sinking of the HMS Aldenham. After we reached the area, and

after some uncertainty because of changes in coastal features, he

said, “It’s here.” We threw a moored signal at

sea; for about another hour of circle patterns the echo sounder

continued indicating a flat bottom at 82 meters (270 feet) below

the surface, but finally it “jumped up.” The Aldenham

wreck was located at a distance of 700 meters (2310 feet) from the

presumed bow section. The old fisherman’s face relaxed in a

smile; for the previous hour he had been thinking that he was

“too old and did not have a good memory.”

Dessa C. Provenzani |

Dessa C. Provenzani |

That afternoon two teams prepared to dive the wreck. The first team

was to do a general survey, and identify a specific point on which

to affix the bronze plaque; the second team would then attach it

with a chain. The attachment point we were searching for was the

torpedo tubes platform. This platform was used as an assembly point

for briefing the crew or for specific ceremonies. Standing on that

point, fifty-eight years earlier, a military priest officiated the

burial at sea of fifty crewmembers of the Royal Navy cruiser HMS

Arethusa, killed during a bomber attack in open sea. That episode

surfaced during our research and particularly touched us. We

thought that that point could represent the heart of the ship and

where we would place the plaque. The dives revealed this to be

impossible.

The wreck lies upside down. It is the stern section of the ship, and measures about 50 meters (165 feet) in length. The zone of breaking, ahead of the engine room, is driven into the mud at 82 meters (270 feet). The wreck sits in an unusual diagonal position, sustained by her superstructures, with her propellers and helm at 67 meters (221 feet) of depth. We placed the plaque on the bottom, under the hull, in a sort of niche formed by the ship’s superstructures and the sea floor. The dives on the HMS Aldenham wreck marked the end of the project, and of the WDS searches in that area.

The following year, WDS organized another research project around the Kriegsmarine Ausland Flotilla. This time eight divers were involved in a seven-day effort aimed at locating the ships sunk during operation Frechdachs, in February of 1944. The base of the project was the Croatian island of Lussino, where a mixed gas filling station and a field hyperbaric facility were set up.

This time the divers were not so lucky. During over thirty hours of surveys with an echo sounder, only two wrecks were found 3.5 miles apart from one another on the flat sandy bottom, at depths of 60 (198 feet) and 63 meters (208 feet). They were neither the Kapetan Diedrichsen nor the corvette UJ-201.

The two units found were two small military vessels of the same type; they had been completely unrigged before sinking. The two propellers of each unit were missing, cut at the point where the shaft comes out from the hull. Both bridges were completely empty and clean, and the base of a missing gun was clearly visible on the bow deck of each wreck. Based on form and dimensions, we think that these were Italian or German motor minesweepers, taken over by the Yugoslavians at the end of the war, and used as artillery targets after being unrigged.

The armed freighter Kapetan Diedrichsen and the UJ-201, former Italian Egeria of the Gabbiano Class, still lie undiscovered on the bottom of the sea and will be the target of future searches by WDS.

Copyright ©2003 Global

Underwater Explorers.

All rights reserved.